The First Chapter of "Generations: Life Beyond the Individual"

I have been thinking a lot about how we might shift our thinking and ways of life to take on a generational philosophy. It is an important next step in our development as a species. Thanks for reading.

Chapter 1: The Spirit of Generational Thinking

“Tomorrow we will do beautiful things.” ― Antoni Gaudí

Several years ago, as a tourist in Barcelona I visited the Basílica de la Sagrada Família (the Basilica of the Holy Family); Antoni Gaudí’s gothic art nouveau architectural masterpiece. It’s an unusual and impressive structure whose saguaro cactus spires stretch toward the sky over Barcelona. Gaudí’s original design calls for eighteen spires, each representing the twelve apostles, the four evangelists, the Virgin Mary, and Jesus Christ himself, represented, naturally, by the tallest spire, yet to be built. It has been, since its inception in 1882, a work in progress. The remaining construction will not be completed until 2032, 150 years after it began.

As a structure, La Sagrada Familia is striking. At a distance you are drawn to it: a manifestation of the Holy Spirit in stone, a testament to faith. As you enter you are dwarfed by its massive supporting columns. The vaulted ceilings of the central nave rise 148 feet above the stone floor.

Even as it awes and seems to have grown in place like a vast vault of stone trees, La Sagrada Familia is manifestly the collective work of individual human beings, from the Catholic patrons who raised the original funding, to the masons and glaziers who chiseled each block of stone and created each stained glass window. Even the 3 million tourists who visit annually contribute to its creation with their admission fees. Many hands and hearts directed to this effort over a century.

Although Antoni Gaudí is most notable as La Sagrada Familia’s architect, at the time of his death the basilica was only 15-25 percent complete. It is a project that spans individuals and generations. Multiple lifetimes are required for its development and one can expect it to persist for many lifetimes more, perhaps even for thousands or tens of thousands of years it will stand as a monument to generational effort.

This aspect of it, as a project, is what struck me most. I don’t think I had, until that moment, considered the mindset required to initiate and contribute to a project one would never see completed. What might motivate such a man? We can make a few assumptions. Perhaps, beyond creative ambition, there was a religious motivation or a community motivation at work in its conception and construction. But even as a believer, did Gaudí’s religious convictions or community identity confer some sort of creative super power that death could not intimidate? Aside from the generational timeline of building such a monument, the size, scope, and complexity of the building project is overwhelming. This monument-building for the ages, dedicated to faith, bequeathed to eternity, is rare and awe-inspiring. Where else would we find projects that require multiple lifetimes to realize? It is beyond our typical scope of thinking.

“Originality consists of returning to the origin”

― Antoni Gaudí

We now tend to limit our ambitions to the individual life, rarely thinking of or considering the world we leave to others.

The Individual Adrift

As a modern person living in a hyper-individualistic, materialist age, the dominant cultural mode is the immediacy of “Now!” and “Me!”, the focus on the atomic self who stands apart separate from everyone else.

With the exception of the vague apocalyptic apprehensions of the environmental movement, we lack a culture that expresses an obligation to either the past or the future. Even our preoccupations with aspects of the past or the future are used to fuel the demands of the present.

We use history not as a way to understand the world before but as a way to reimagine and recreate the present, to tell us a story about ourselves and to justify our own modern superiority. For example, it is commonplace to look backward at negative aspects of the past, such as the barbarism of war or slavery, as a way to feel confident about our own current values and to paint a picture of the March of Progress. The present world is seen as a world that is always superior to the past, in every way.

We feel no deference or responsibility to the past nor do we seek to provision a better world for our descendents. At most, we try to anticipate the future, to inform plans in the present.

But, we do not think in terms of generations: those who came before and those who will come after. What should we do now to promote a legacy for them? They have no voice.

Consideration of the people who inhabit the past and future imparts an obligation; to consider our place, our responsibilities; the consequences of the decisions we make. The weight of the past can also overshadow our own individuality and we respond by turning away. The result is that we become isolated from our own stories; disconnected and atomized individuals adrift in an endless present.

In considering Gaudí and La Sagrada Familia, I realized I had missed something fundamental. Although nominally Christian I had always tended toward an intellectualized shrugging agnosticism. But, now I wondered if I had been stumbling around blind and senseless, marooned in the tepid shallows of the modern world and its myopic attention to the here and now.

In this idea of Continuity between Past, Present and Future were whole new geographies of thought and experience to consider: the humility of the creator, the quiet faith of the believer, the individual who allows himself to shrink before the timeless Creation humbly working toward a larger project that absorbs him but in doing so creates a place for him in the grandeur of its achievement.

Who would not want to be part of something timeless and important? What would life look like if I stopped considering myself as the protagonist in my own small story and started seeing myself more as a supporting player in a larger, multi-generational epic? How would my values change? How would I make decisions differently if I felt an obligation to contribute to the future?

The End of Belief

This essentially religious perspective felt at odds with everything else in the world. We do not operate on the injunctions of Faith. We do not build new cathedrals or temples, nor even monuments. La Sagrada Familia feels alien because the materialist world has prevailed, at least for the moment. Not only do we not believe in God, but we no longer believe in anything at all. Our moral and religious senses, our sense of wonder, have withered away. A world aflame with the ardor of ideas and belief is now populated with ghosts and relics that have no meaning.

We constrain our thoughts to only those subjects that satisfy the physical senses or our need for mental stimulation. Rather than belonging to a belief tradition that establishes a foundation for life, we receive our values from the media, films, books, music, and other cultural products excreted by multinational corporations.

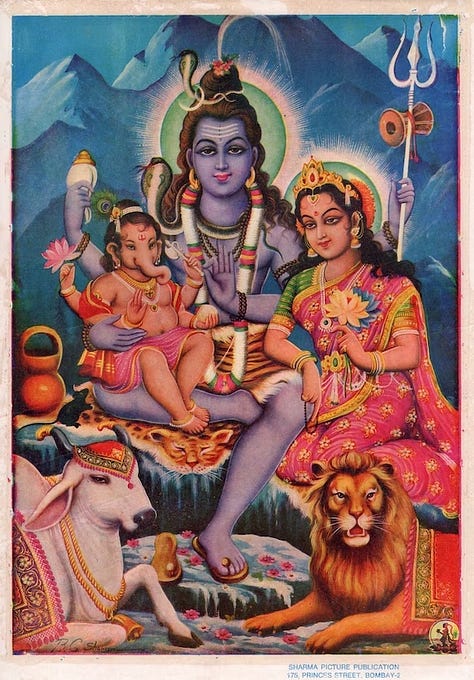

The Marvel comic book pantheon has replaced the Greco-Roman or Hindu pantheon. The gods of the Universe are packaged, adulterated and sold back to us. As a result, many children know more about Spiderman or Star Wars than they do their own myths and cultures, religious lessons, history and folk stories that are foundational to their own cultural story.

The consequence of replacing this timeless commonwealth of stories, traditions and values with ephemeral consumer counterfeits is that we have become dislocated from our own organic vernacular culture. Our cultural memory starts and ends with consumer products created by vast corporations who impose top down values (if they promote values at all).

The goal of consumption is ephemeral pleasure and thus the highest aim of life becomes the attainment of a pleasure that cannot fully satisfy. Beyond the ethos of consuming and acquisition, Capitalism has little to offer. It lacks a moral or ethical perspective. It says nothing about what life is or should be about.

As a result of this substitution for cultural counterfeits, where we once inherited a connection to our own past and a larger moral framework that placed us in a web of relationships, we are now atomized and disconnected. Spiritual life is flattened. All moral lessons become anodyne and watered-down to allow the smooth operation of the marketplace, necessarily because no other values can be allowed to compete with the highest value of pleasure-seeking that undergirds consumerism.

All of this might be acceptable, except that individualistic consumerism cannot provide answers to key questions about existence. What is the meaning of life? Why are we here? Why do we suffer?

Because we lack a framework for placing ourselves in a larger intergenerational context beyond the individual life, we are powerless against real suffering. Suffering cannot be acknowledged to exist in a consumer world of pleasure-seeking. Suffering is a reproach of our centrality as individuals. To acknowledge that we suffer is to acknowledge that we are powerless. And, if we are powerless, what’s the point?

We have been trained only in the exercise of pleasurable consumption. Our spiritual senses have become atrophied and vestigial. We can no longer fly.

One can sense the connections here: the individual vs. the family or community. There are connections between these elements: faith, time, generations, family, humility, creation, imagination, nature, life. There is a unifying thread.

Life is created and perpetuates itself through creation. Our experience of life presents the fact of timelessness. We arrive as guests into an eternal Immensity and we soon enough depart but what we contribute lives on. The artist creates and this creation has a being that resembles procreation. Creation is the essence of life. How can we incorporate this aspect into our daily lives?

The answer, in part, lies in shifting our thinking from the individual to the family and from the family to the community. All layers comprising the structure of a whole.

Family is the relation of the individual creations to one another. Families persist in time over generations as these relations supersede the individual. Humility is the recognition of these unchanging laws of existence. Faith is the sense of hope and significance that the ephemerality of one’s life adds up to something meaningful.

What I call “Familyism” is the essence of how we begin to shift this thinking. I address this in the following chapter.

If you want to help in this project, I would appreciate your feedback and please share with others. If you are interested to read more, become a paid subscriber. Subscribers will receive additional chapters.